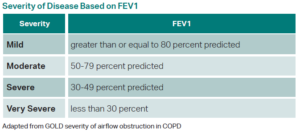

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a chronic disease of the lungs caused by inflammatory and structural changes of the small airways and parenchyma of the lungs that result in chronic airflow obstruction and gas trapping. In 2019, the global prevalence of COPD was estimated to be 10.3 percent, and COPD is responsible for about three million deaths per year globally.2,17 COPD is diagnosed by spirometry with a forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio of less than 0.7.4 Acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD) are a common presentation in emergency medicine. Exacerbations accelerate disease progression and can lead to increased rates of hospitalization and death.4,14 As these exacerbations represent a critical point in the progression of COPD, it is important for emergency physicians to understand the approach to diagnosis and management of AECOPD.

Initial Evaluation

As with all critical emergency medicine patients, AECOPD patients should be placed on cardiac monitoring and pulse oximetry, and initial evaluation should focus on vital signs and assessment of airway, breathing, and circulation.

Clik here to view.

Click to enlarge.

History

The history should focus on assessing for the possible trigger, confirming AECOPD, assessing severity of baseline disease, and evaluating for symptoms that may point toward an alternative diagnosis. Common triggers include infections, recent medication changes, colder weather or air pollution, and medication non-adherence. Presenting symptoms of AECOPD include increased shortness of breath, increased frequency of cough, and increased volume of sputum or change in sputum color or consistency. Exacerbations are more commonly caused by viral infections; however, bacterial infections need to be considered. AECOPD associated with purulent sputum production is most commonly due to bacterial infection.

Clik here to view.

Click to enlarge.

Determining the severity of the patient’s baseline COPD is important in guiding management of the exacerbation. Reviewing the patient’s most recent FEV1, if it is available, is an easy way to determine the severity of obstruction. Other historical items that can assess for severity of disease include history of intubations, frequency of exacerbations and hospitalizations, home O2 flow rate, and comorbidities. Recent hospitalization is important for choosing antibiotic coverage.

And, finally, patients with a history of COPD frequently present to the emergency

department with dyspnea. Although dyspnea in this setting likely represents an AECOPD, other emergent differentials must be considered. Some of the critical differentials include pulmonary embolism, acute decompensated heart failure, pneumonia, pneumothorax, and acute coronary syndrome. Sudden symptom onset suggests pulmonary embolism or pneumothorax. Signs and symptoms of systemic infection (e.g., fevers, chills) suggest pneumonia. Anginal chest pain, chest heaviness, or evidence of fluid overload suggest acute coronary syndrome or acute decompensated heart failure.4,10,11

Physical Exam

Vital sign abnormalities in AECOPD include tachypnea, tachycardia, hypoxemia, and fever if an underlying infection is present. Physical exam should focus on assessment of work of breathing and the cardiopulmonary system. Work of breathing can be assessed by looking for tachypnea, tripoding, accessory muscle use, inability to speak in full sentences, and decreasing level of consciousness. Wheeze and decreased air entry on auscultation are common findings in AECOPD. Focal lung findings (focal rales or dullness to percussion) point more toward pneumonia. Unilateral decreased breath sounds can indicate pneumothorax. An S3 on cardiac auscultation, jugular venous distension, or lower extremity edema suggests heart failure.4,10,11

Diagnostic Workup

Although AECOPD is largely a clinical diagnosis, some diagnostic modalities are useful to help rule in or rule out alternative diagnoses.4,10,11

- Chest X-ray is used to evaluate for pneumothorax, pulmonary edema, or pneumonia.

- Ultrasound evaluates for global heart function, right heart strain, pulmonary edema, and lung sliding.

- Complete blood count evaluates for leukocytosis or anemia.

- Basic metabolic panel evaluates for electrolyte abnormalities.

- ECG evaluates for dysrhythmias, acute coronary syndrome, or signs of right heart strain.

- Viral polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can be considered in evaluating for a viral infection, such as COVID-19 or influenza.

- Clinical decision tools such as PERC +/- d-dimer or CT angiography of the chest are used if pulmonary embolism is considered likely.

- Brain natriuretic peptide can be considered to evaluate for heart failure.

- Troponin can be considered to evaluate for acute coronary syndrome.

- Blood gas (venous or arterial) can be considered to evaluate for extent of hypercapnia or in patients with decreased level of consciousness to assess for hypercapnic encephalopathy.

Management

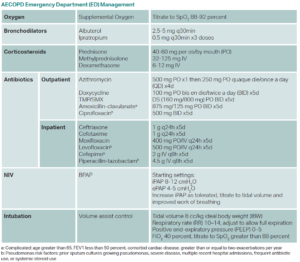

Oxygen

- Supplemental oxygen should not be withheld despite risk of hypercapnia.4

- Hypercapnia worsens with higher oxygen saturations largely because of increased shunting of blood away from well-ventilated alveoli into poorly ventilated alveoli.1

- Titrate to oxygen saturation of 88-92 percent.1,4,11

- Common methods of oxygen delivery:

- Nasal cannula (1-6 L/min, about 24-45 percent FiO2);

- Heated high flow nasal cannula (10-60 L/min, 21-100 percent FiO2);

- Simple mask (6-10 L/min, 35-50 percent FiO2);

- Venturi mask (2-15 L/min, 24-60 percent FiO2); and

- Non-rebreather (10-15 L/min, about 80 percent FiO2).8

Bronchodilators

- Albuterol 2.5-5 mg plus ipratropium 0.5 mg every 30 minutes x3 doses;

- No significant difference in FEV1 improvement between metered dose inhalers (MDI) and air-driven nebulizers; and

- Can be administered in-line through high-flow nasal cannula or BPAP. 4,10,11,12

Corticosteroids

- Systemic corticosteroids shorten recovery time and improve FEV1, oxygenation, risk of early relapse, treatment failure, and length of hospitalization.4,14

- Oral prednisone 40-60 mg (or equivalent) daily for five days.4,11

- Oral corticosteroids are as effective as intravenous steroids, but a one-time dose of intravenous methylprednisolone 125 mg in the ED is useful for patients who obviously cannot tolerate oral medications.4,6,11

Antibiotics

Antibiotic use for AECOPD patients remains a contentious topic; however, data suggests AECOPD patients requiring admission, particularly to the ICU, should receive antibiotics.10,12 It’s important to note that there is still no consensus on which discharged AECOPD patients require antibiotics and which antibiotics are the most effective; however, limited data suggests outpatient antibiotics reduce risk of treatment failure, shorten recovery time and hospitalization duration, and increase time between exacerbations.4,14 GOLD guidelines recommend antibiotics in patients with three of the cardinal symptoms (increased dyspnea, sputum volume, and purulent sputum), or purulent sputum plus another of the cardinal symptoms, or in those requiring mechanical ventilation (invasive or noninvasive). While the American Thoracic Society (ATS) agrees that purulent sputum is associated with the need for antibiotics, ATS also suggests considering disease severity when deciding which discharged AECOPD patient gets antibiotics.14 Overall, those with non-severe baseline COPD, no significant comorbidities, minor AECOPD symptoms, and no purulent sputum can likely be discharged without antibiotics.4,7,10,14 There is also emerging data evaluating C-reactive proteins (CRP) cutoffs as a potential guide for antibiotic prescription.7

In uncomplicated discharged AECOPD patients who are receiving antibiotics, data suggests initial empiric azithromycin, doxycycline, or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole are all appropriate options.3,4,7 Fluoroquinolones and amoxicillin-clavulanate were shown to be more effective than macrolides and many of the cephalosporins.3 Those who are elderly (greater than 65 years) or have severe disease (FEV1 less than 50 percent), comorbid cardiac disease, or frequent exacerbations (greater than or equal to two per year) are considered higher risk, and a course of amoxicillin-clavulanate should be considered.3,4,7 AECOPD patients with pseudomonas risk factors (prior sputum cultures growing pseudomonas, severe disease, multiple recent hospital admissions, frequent antibiotic use, or systemic steroid use) should receive pseudomonas coverage with a fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin or levofloxacin.3,4,7,14,16 GOLD guidelines recommend a less than or equal to five-day course of antibiotics.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Non-Invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation (NIV)

- Bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) preferred over continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) for AECOPD.

- NIV decreases mortality and intubation rate and improves oxygenation, respiratory acidosis, and work of breathing.4,14

- BPAP initial settings:

- Inspiratory positive airway pressure (iPAP): 8-12 cm-H20

- Maintain iPAPs less than 20 cm-H2O to avoid gastric distension.

- Expiratory positive airway pressure (ePAP): 4-5 cm-H2O

- Titrate driving pressure (iPAP–ePAP) to adequate tidal volume and improved work of breathing via increased iPAP.11,14

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Click to enlarge.

- Inspiratory positive airway pressure (iPAP): 8-12 cm-H20

- Consider light sedation for patients who cannot tolerate NIV.4

Intubation

- No specific recommendations on which induction agents to use. Some evidence from asthma literature suggests ketamine has some bronchodilatory activity.5

- Some evidence suggests using larger diameter endotracheal tubes to avoid increasing airway resistance.11

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Click to enlarge.

- Ventilator settings should be targeted toward avoiding auto-PEEP and permissive hypercapnia.15

Disposition

Discharge

Generally, patients with mild to moderate symptoms on presentation, good response to ED management, no new or increased supplemental oxygen requirement, and no desaturation with ambulation can be considered for discharge. It’s good practice to address several areas of outpatient management prior to discharge to help prevent recurrence of exacerbations and ED bouncebacks: Inhaler technique should be assessed; the patient’s current maintenance therapy and their understanding of this therapy should be checked to ensure the patient is using his or her medications appropriately; counseling on smoking cessation should be performed; and close follow-up should be arranged for the patient. Good discharge instructions and strict return precautions should be provided.4

Admission or Placement in Observation Unit

Patients who present with severe symptoms, show evidence of acute respiratory failure (e.g., respiratory rate greater than 24, heart rate greater than 95, use of accessory muscles, new or increased supplemental oxygen requirement, hypercapnia above baseline, altered level of consciousness), have symptoms refractory to aggressive initial medical management, have serious comorbidities, or have a lack of home support should be strongly considered for admission or at least placement in an ED observation unit if available.4

Those with severe dyspnea, significantly decreased level of consciousness, persistent or worsening hypoxemia and/or severe or worsening respiratory acidosis (e.g., pH less than 7.25) despite supplemental oxygen and NIV, respiratory failure requiring intubation, or hemodynamic instability requiring vasoactive medications should be admitted to an intensive care unit for further careful management.4

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Dr. Glauser is professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University at MetroHealth Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland.

Dr. Glauser is professor of emergency medicine at Case Western Reserve University at MetroHealth Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view. Dr. O’Hora is an emergency medicine physician in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

Dr. O’Hora is an emergency medicine physician in Cleveland Heights, Ohio.

References

- Abdo WF, Heunks LMA. Oxygen-induced hypercapnia in COPD: myths and facts. Crit Care. 2012;16(5):323.

- Adeloye D, Song P, Zhu Y, et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of, and risk factors for, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in 2019: a systematic review and modelling analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2022;10(5):447-458.

- Canut A, Martín-Herrero JE, Labora A, et al. What are the most appropriate antibiotics for the treatment of acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? A therapeutic outcomes model. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2007;60(3):605-612.

- Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2023 report). https://goldcopd.org/2023-gold-report-2/. Updated Feb. 17, 2023. Accessed May 19, 2024.

- Howton JC, Rose J, Duffy S, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of intravenous ketamine in acute asthma. Ann Emerg Med. 1996;27(2):170-175.

- Leuppi JD, Schuetz P, Bingisser R, et al. Short-term vs conventional glucocorticoid therapy in acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: the REDUCE randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;309(21):2223-2231.

- Miravitlles M, Moragas A, Hernández S, et al. Is it possible to identify exacerbations of mild to moderate COPD that do not require antibiotic treatment?Chest. 2013;144(5):1571-1577.

- O’Driscoll BR, Smith R. Oxygen use in critical illness. Respir Care. 2019;64(10):1293-1307.

- Parrilla FJ, Morán I, Roche-Campo F, et al. Ventilatory strategies in obstructive lung disease. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;35(4):431-440.

- Quon BS, Gan WQ, Sin DD. Contemporary management of acute exacerbations of COPD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest. 2008;133(3):756-766.

- Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski JS, Ma OJ, et al, eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. Ninth edition. New York, N.Y.: McGraw-Hill Education; 2020.

- van Geffen WH, Douma WR, Slebos DJ, et al. Bronchodilators delivered by nebuliser versus pMDI with spacer or DPI for exacerbations of COPD. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;2016(8):CD011826.

- Vollenweider DJ, Frei A, Steurer-Stey CA, et al. Antibiotics for exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;10(10):CD010257.

- Wedzicha JA, Miravitlles M, Hurst JR, et al. Management of COPD exacerbations: a European Respiratory Society/American Thoracic Society guideline. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(3):1600791.

- Weingart SD. Managing initial mechanical ventilation in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(5):614-617.

- Wilson R, Jones P, Schaberg T, et al. Antibiotic treatment and factors influencing short and long term outcomes of acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis. Thorax. 2006;61(4):337-342.

- Naghavi M, Wang H, Lozano R, et al. Global, regional, and national age–sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2015;385(9963):117-171.

The post Evaluating Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease appeared first on ACEP Now.